Traditionally made from hira silk, a fine-textured and durable fabric, hakama are worn on the lower part of the body and resemble wide-legged trousers. They can be split into two legs or un-split, forming a skirt. The bifurcated form of hakama is sometimes referred to as umanori, meaning "horse-riding hakama" in Japanese is more frequently worn by men than women, with the exception of the practice of martial arts. Hakama are ankle-length, allowing an individual’s feet to show, and rise to the small of the back where there is a firm, trapezoidal board known as a koshi-ita. The hakama have four straps, two on the front of the garment and two on the back, which are wrapped around the waist and koshi-ita before being tied in a formal knot just below the navel. They are traditionally worn over a kimono and sometimes are covered with a thigh or hip length jacket known as a haori.

Figure 1: Front |

Figure 2: Back |

|

|

In Ken No Koe, or The Voice of the Sword, Kendo master Masataka Inoue identified meanings for the pleats in hakama. They are: Chu (loyalty), Ko (justice), Jin (compassion), Gi (honor), and Rei (respect). In other forms of martial arts, seven pleats are used. Hakama are worn for formal occasions by men, and also by women, so the meaning of the pleats varies considerably due to purpose and occasion.

There are five pleats on the front of the bifurcated hakama pictured in Figure 1 above, with three pleats located on the left leg and two pleats are located on the right, ranging in width from approximately 3 to 6 centimeters. There are also two 13 centimeter pleats located on the back of the hakama, as seen in Figure 2 above, indicating the split of the pant legs. This layout is by no means the same in every garment, as the hakama change in style and form, which has been the case for several centuries.

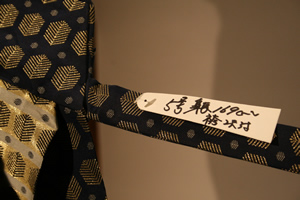

Though the placement of hakama pleats is asymmetric, the pattern that adorns them is extremely uniform. There are roughly thirty rows of geometric, rectilinear shapes sewn into the garment about half a centimeter apart from one another, with smaller versions of these same shapes located in the spaces between rows. From a distance this gives off a sort of checkered appearance, however, upon looking closely, the delicate details of this hakama are revealed. The larger shapes, which measure to be about 2 centimeters tall and 1.75 centimeters wide, resemble some sort of tree or leaf structure with ten thin lines stretching out diagonally from a center stem. The smaller shapes, whose widths and heights are both .5 centimeters, do not have a stem but have four lines stretching out from their centers where stems would have been on each of their sides.

Figure 3: Fabric Exterior |

Figure 4: Fabric Interior |

|

|

It is entirely possible that the image used to pattern these hakama is a family crest, or kamon, of the same sort that is used to embellish both the left and right chest of the haori. If so, it could be a floral symbol such as a tree, flower, or leaf; or a tool symbol, such as arrow fletching. The most identifiable kamon is a representation of a paulownia flower; it grows on trees native to East Asia that produce wood that is highly prized in these regions.

Though one’s eye is immediately drawn in by the pattern of these hakama, their coloring is equally as beautiful and intriguing. The garment is made from deep blue, gold, and cream silk brocade. Brocade patterns can be woven by hand, however the process is extremely lengthy and requires years of mastery to achieve as a high a level of quality as is present in this pair of hakama. The specific type of mechanized loom able to achieve this level of detail is known as the Jacquard loom, first demonstrated in the early nineteenth century by French Inventor, Joseph Marie Jacquard. Every row of stitching in a garment woven by a Jacquard loom is controlled by a punch card which gives it specific instructions on when and where to weave certain threads into a piece of clothing.

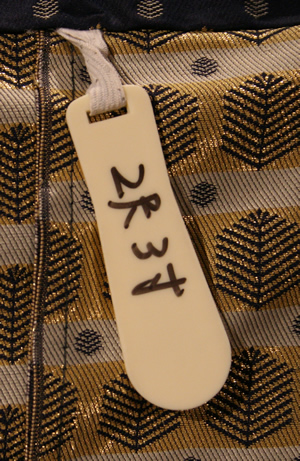

These hakama have never been worn; the tag, as seen in Figure 5 below, remains on the interior of the garment attached just below the koshi-ita. They are intended to be worn by a man and measure roughly 100 centimeters from the base of the koshi-ita to the floor. Both sets of times are 3 centimeters wide; the front two ties are 160 centimeters long and the back two are 93 centimeters long. The girth of the garment is not especially relevant, seeing as the waist size can be manipulated by tightening or loosening the hakama straps when tying it around one’s body. They are umanori, though they would have most likely been worn at Japanese tea ceremonies and weddings instead of while riding horses.

Figure 3: Koshi-ita |

|

The trapezoidal koshi-ita of this hakama has a 25.5 centimeter base, 17.5 centimeter top, and 9 centimeter height. The divide between the pant legs occurs approximately 40 centimeters from the base of the koshi-ita, allowing for quite a bit of unrestricted space in the upper thigh and hip regions. This amount of room is considered quite necessary for certain martial arts positions involving deep squats that showcase the aesthetic beauty of the hakama and strength of the practitioner. If the bottom of this specific pair of hakama was stretched out to full capacity, creating an un-pleated circular shape on the floor representing the full stretches of its pant legs, it would have a circumference of 342 centimeters. When compared to the 100 centimeter height of the hakama overall, it is easy to visualize how much movement the fabric of this wide-legged garment can capture when its wearer is in the midst of activities ranging from walking to advanced physical activity. It will give off the same effect as a circle skirt mid-spin when an individual is turning, which oftentimes leads people to the false conclusion that all hakama are skirts, or un-split. In fact, the hakama most commonly seen by tourists are umanori, as the un- split version is worn most frequently by women, who do not wear hakama regularly at all.

At the bottom of the koshi-ita inside the center back of the hakama is a hera (see Figure 4 below) which helps hold the hakama in place.

Figure 4: Hera |

Figure 5: Price Tag |

|

|

Hakama have been an important part of Japanese culture for centuries and have never stopped evolving in both style and symbolism. These garments are not only able to provide details about an individual’s background or whereabouts, but can symbolize facets of different philosophical schools as well as showcase principles of Japanese design and aesthetic culture.

© Kim Donofrio, 2017