La Belle Epoque Bodice

La Belle Epoque was a period of fashion from 1890 to the beginning of World War I. Ready-to-wear was more accessible to the middle class, and the bustle, which was the fashion of the 1870s and 1880s, disappears. Due to the smaller sleeve heads, the subtle pouter pigeon blousing, and the natural waist, the bodice falls decisively in the middle of the La Belle Epoque period, circa 1898.

Indicators of the period include the slightly subtler leg-o-mutton sleeves, the stand collar, the waist of the bodice landing at the natural waistline, and how the closures resolved themselves. As Jean Hunnisett says on page 144 of her book, Period Costume for Stage & Screen, "...the back of the bodice was mounted in with the foundation while the front foundation fastened independently down the centre. The bodice fabric was then arranged in whatever was the style of the bodice." The scale of the sleeves of the period went from the enormous gigot in 1894 to tasteful fullness in 1900, although there were variations in sleeve scale within each year.

Figure 1: Bodice Front |

Figure 2: Bodice Back |

|

|

Bodice Construction

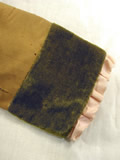

This bodice, as seen in Figures 1 and 2 above, is made of a lightweight butterscotch wool gabardine with avocado green silk velvet cuffs and covered buttons. It has a sailor collar with a stand made in that same velvet. The pouter pigeon bib front is made of light pink silk faille with small ruffles of the same faille at the cuffs and neckline. The garment is flat-lined with brown linen. Taking into account the cut of the garment and the kinds of fabrics used, this bodice was the top half of a day dress ensemble, and would have been worn over a corset.

The bodice closes at true center front with thirteen hooks and eyes, as seen in Figures 3 and 4 below. Both the hooks and the eyes are sewn on the underside of center front and set back from the fold of the lap about 3/4". Because of this, the laps do not lay nicely over one another or butt up against each other, and as a result the closure does not resolve in a graceful way. The hardware is clumsily stitched on using white heavy-duty thread and there is no attempt to hide the stitching, which suggests that these are not the original closures. The pouter pigeon bib closes on the left side front, and although there is no evidence of closures (i.e. scars on the fabric where closures once were, or any residual threads) it can be assumed that it originally closed with hooks and eyes. The velvet stand collar wraps to the left neck point where it would fasten, presumably, with a hook and eye, although again there is zero evidence of closures, threads, scarring, etc.

Figure 3: Closure: Hooks |

Figure 4: Closure: Eyes |

|

|

The front structural foundation has two waistline darts and the shoulder seam extends beyond the true shoulder line. The side seam also extends beyond the true side seam line toward the back. Both of these construction choices are subtle, not exaggerated. The false fronts of the bodice have slight shaping at the princess line and the sailor collar is attached only to this piece along with the buttons. There is evidence of slip stitching to stabilize the false fronts to the foundation. The pouter pigeon bib is stitched to a foundation of the same linen flat-lining used in the rest of the bodice to help control the fullness, but the faille pouter pigeon is not flat-lined. The bib is permanently stitched to the right side of center front and closes to the left.

The back bodice is a fiddle back configuration comprised of six shaped panels. Starting at the side seam, the waistline gradually dips below the natural waist to a point three inches below the natural waist at center back. The waist hem is finished with a 1 1/2" piece of bias gabardine that is turned up and fell stitched. The waistline darts, center front foundation closure, center back and curved side back seams are all boned with uncovered celluloid bones which are cross-stitched to the seam allowance. This cross-stitching is done in the same white thread with which the existing hooks and eyes are sewn.

The sleeves are cut in two pieces with a leg-o-mutton sleeve cap. The cap is pleated by hand and stabilized with a running stitch before being set into the armscye by machine and then hand-overcast. The pleating and hand-stitching in the armscye can be seen in Figure 5 below. It is interesting to note that the unaltered sleeve pattern was used in the mockup for the reproduction, and was three inches too long for the model, who has a 22 1/4" sleeve length. It could be argued that the sleeves were pushed up on the biceps to create ruching or a fashionable fold, but there is no evidence of creasing in the fabric or anything else that might suggest this theory. It can be assumed that a woman with a 23 1/2" waist would be quite petite in height, and therefore she pushed up her sleeves or had exceptionally long arms.

Figure 5: Armscye |

|

The sailor collar is comprised of four pieces – two corners or "toes" – have been pieced into the back collar. This is presumably because this velvet was cut down from another garment and there was not enough yardage to cut in one (although there is no scarring from old stitching that would suggest this). The center back of the collar is seamed on the bias. This was done to cause the straight grain to lie on the front neckline, and also so the pile of the velvet would be going in the correct direction. This is important because pile fabric catches the light in different ways depending on its orientation. There is no roll in the collar neckline, which is an odd choice. The result is that the collar does not lift away from the bodice and lie over the shoulders in an attractive manner, but buckles at the sides when it meets the sleeve heads.

Figure 6: Stand Collar and Interior |

|

Damage

The garment has a reasonable amount of damage from normal wear and tear. The wool and silk have moth holes, but the silk shows no evidence of shattering. The velvet is in very good condition, as is the linen flatlining. The most damage is in the underarm area, where perspiration has accelerated the fabric’s deterioration. There are no tears apparent from rough handling or wearing of the fabric in high-stress areas such as the elbow.

Color

The velvet is a vibrant green, which raises the question of whether or not the dye is carcinogenic. Invented in 1775 by Wilhelm Scheele, Scheele’s Green was by far the most popular green dye in wallpapers, apparel fabrics and other textiles well into the 19th century. Because arsenic was a key component, the most saturated greens were invariably toxic and were known to cause skin lesions, illness and death. Although it is difficult to find a concrete date when Scheele’s Green ceased being used in apparel fabric, the general public was aware of the dye’s sinister properties in the 1860s and 1870s, according to Victoria Finlay who discusses Scheele’s Green on pages 277-278 of her book Color: A Natural History of the Palette. The advent of synthetic dye seems to have made arsenic green obsolete by the 1880s, although it continued to be manufactured into the 1900s. Because this bodice was constructed circa 1898, it can be safely concluded that the dyes used on the velvet are synthetic.

Measurements

| Bust | 32 1/2" |

| Waist | 23 1/2" |

| Center front length | 15" |

| Center back length | 18" |

| Neck opening | 12" |

| Sleeve length from shoulder point to wrist | 25" |

| Cuff circumference | 9" |

| Button diameter | 1 1/4" |

© Max Epps, 2016