Garment Analysis

By the later half of the 19th century, the frock coat had gained widespread popularity among the upper class. Brought into fashion by Prince Albert, the coat became a primary style of body coat worn into the early 20th century. The body coat is described as a garment that fits the body closely at the waist. There are a number of body coat styles, the two at the forefront being the morning coat and the frock coat. The frock coat could be single or double-breasted, the latter being referred to as a Prince Albert frock, accordint to Robert Doyle on page 150 of The Art of the Tailor. In the early 1900s, the frock coat was worn by the socially affluent, but also by businessmen. Tailors, by association, established their superiority in the ranks of garment constructors by wearing the frock coat, according to Harry A. Cobrin on page 27 in The Men's Clothing Industry. The popularity of the coat waned, however, as advancements in central heating made the coat more restricting than beneficial to the wearer. Over the lifespan of the frock, the hem lengths shortened from well below the knees to several inches above, as Cobrin writes on page 159.

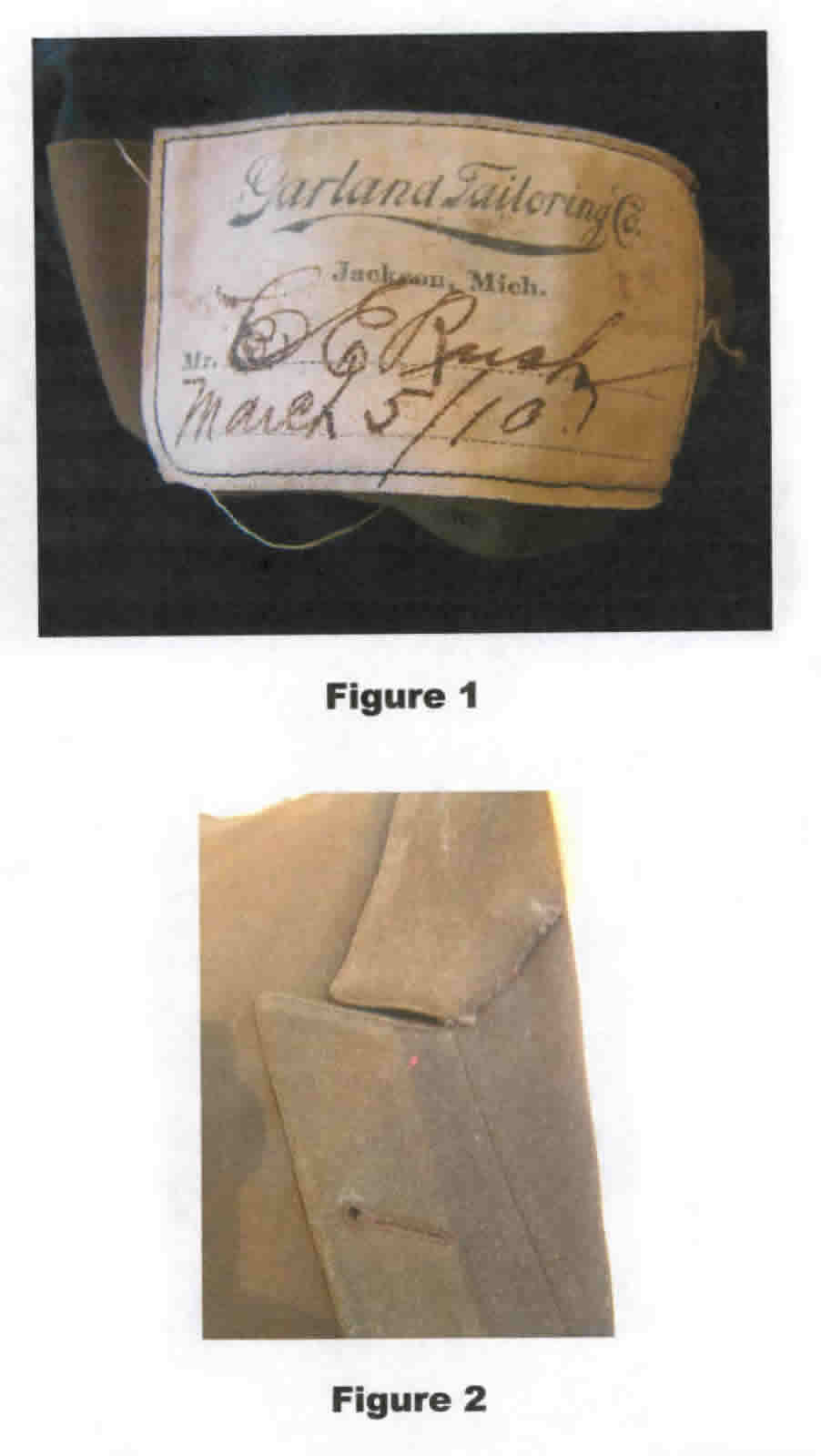

The Garland Tailoring Company in Jackson, Michigan, manufactured this particular frock coat, which was obtained by C. E. Rush on March 5, 1910, as documented in the label reproduced in Figure 1 below.

Label and Lapel |

|

There is a maker's label in the inside breast pocket dating the garment at March 5, 1910. The frock coat is commonly accepted to be "the basic body-fitting coat with a horizontal seam at or near the waist separating the skirts from the upper body" according to Robert Trump on page 58 of The Sartor System of Drafting Historic Men's Wear for the Stage. Other distinctive features of the frock include side back panels, a small knife pleat between the skirt and back piece, and a waist seam that terminates at the back leaving the center back cut as one long piece. This coat includes all of these features.

Damage

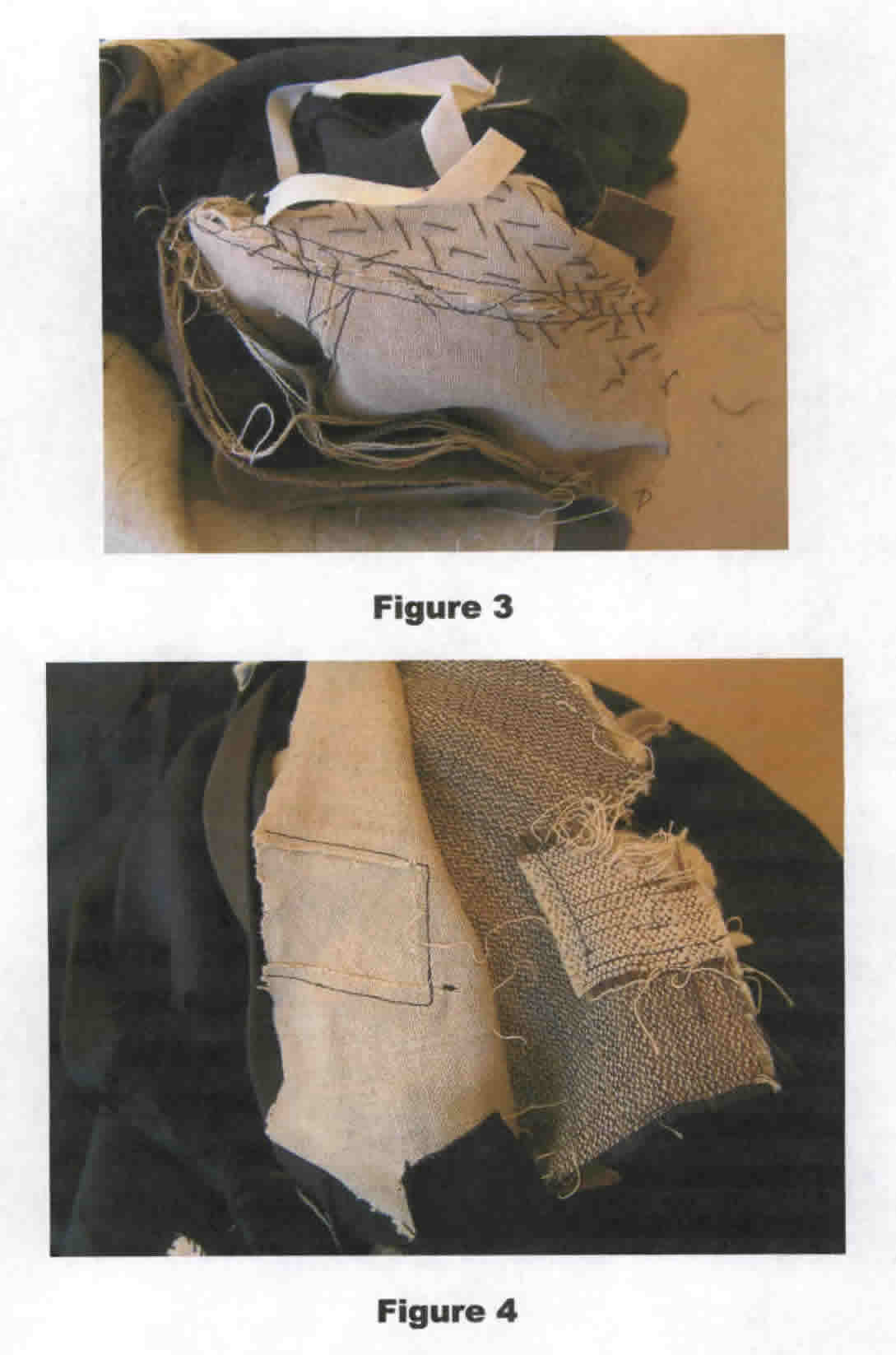

Overall, the coat is in poor condition, presumably a result of poor care, theatrical use, improper storage, and age. Structurally, the coat is severely damaged. Many of the seams are weak or torn. The right shoulder seam has split. Lesser fabric discoloration on a portion of the lapel indicates that a silk faille lining originally ran the lapel facing, as seen in Figure 2 above. The remaining shadow shows that the faille detail extended from above the gorge line onto the collar and also to below the intersection of roll-line and center front. The faille finished at 1 1/4 inches from the edge of the lapel. The faille facing is also likely as the gorge line allowance is overlapped and whip-stitched, which would not be the case were there no other fabric to finish the seam. Both sleeve linings are unattached at the cap and the underarm. The lining is deteriorating at the center back neckline edge and at the seam joining the torso and skirt linings. The hem of the skirt has fallen and is breaking down at the pressed hemline, and the lining is torn throughout the lower portion of the skirt.

The dominant color of the frock was black, although gray and dark blue were acceptable colors. This wool, once black, has faded to an overall shade of green. Years of exposure to both natural and artificial light caused a reaction in the chemical compound used in the fabric's dye process. At the turn of the 20th century, there were many companies producing synthetic dyes, with specific ingredients remaining proprietary information to reduce duplication. By this time, most natural dyes had been replaced by synthetic dyes, as advances made in the industry removed the usage of arsenic and were considered harmless and less expensive, according to Amy Greenfield in A Perfect Red (pages 241 -244). Although the combination of dyestuffs is purely speculative, the components were most likely completely synthetic. Although all red dyes are prone to breaking down, the natural cochineal found in red dyes was not as colorfast as synthetic alternatives. The green shade of the coat is a result of a breakdown in red dyes used in the black color process.

Internal Construction

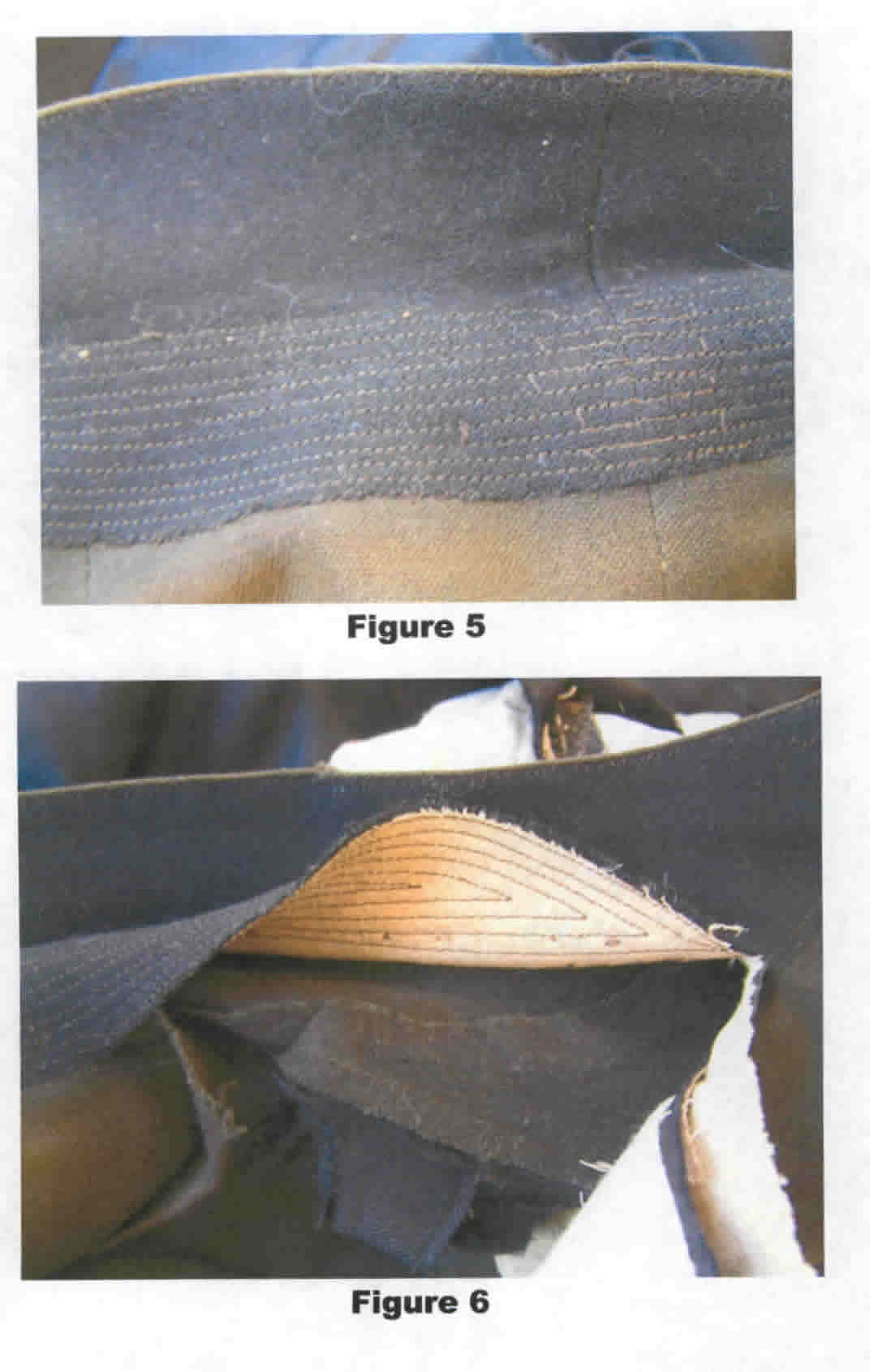

The deterioration of the coat allows for an examination of the intemal construction techniques. As the right shoulder seam is split, the inside plastron is visible through a majority of the coat's chest, as seen in Figure 3 below. The canvas is comprised of three layers. The outermost layer is of heavy canvas similar to duck cloth. The middle layer is a form of haircloth with weft threads of horsehair (results according to burn testing). The warp is a thicker weave of natural cotton fiber. The third layer closest to the body, is a thin baby flannel. Between the haircloth and flannel is a bridle 1 1/2 inches wide of black bias canvas extending from the neckline edge at the shoulder seam which extends the length of the gorge line. In the canvas, there is a combination of machine and hand sewing. The bias ease inserts in the plastron's shoulder are one inch by one-inch squares, as opposed to the "V" inserts described in later tailoring construction manuals (Figure 4). The lapel canvases are overlapped and machine stitched at the center front seam. The revere is hand pad-stitched, with the taping at the roll line also being secured by hand sewing.

Plastron Interior |

|

A layer of thinner felt is used, as opposed to the heavier weight undercollar melton, as illustrated in Figure 5 below. The undercollar felt and French canvas are quilted by machine, and attached to the coat body at the neckline by a hand fell-stitch (Figure 6). The gorge line joins the undercollar at a distance of 1 5/8 inches. Laid flat the lapel is peaked by nearly 2 inches, but lays parallel to the chest line when rolled back onto the coat. The lapel finishes at 2 3/8 inches. There is a seam running the length of center front creating the overlap of the double breast as well as the lapel. The roll line extends from the body of the coat and through this seam into the extension.

Undercollar |

|

On the body of the coat, a one inch dart is taken at the chest level to accommodate further shaping (Figure 7). The center front seam allows the front of the coat to lie smoothly and close to the chest.

Dart under Lapel |

|

The coat lining is basted into the armscye seam allowance with a white cotton basting thread. Although the lining itself is sewn by machine, it is secured to the coat almost exclusively by hand. Almost all seam allowances are sewn at 1/4 of an inch, congruent with the allowance incorporated into many tailoring pattern drafts of the time. One inch is left in the hem, which is presumably the original hemline. The wool is stayed with a strip of tailor's tape along the hem crease. The center back vent seam of the skirt extends by one inch overlapping onto the right side of the skirt. The right side also underlies by one inch, as seen in Figure 8 below. Sleeves of the coat are of standard two-piece construction. Armscyes are smaller with more fullness at the elbow than at the bicep. The back seam falls one inch above the side back seam on the right sleeve, and 11/2 inches on the left sleeve. The inconsistency in the sleeve setting appears to have been a result of the garment making process as opposed to a later alteration.

Coat Back Detail |

|

Pattern

The drafted pattern used to create this coat conforms to theories of male proportion of the day. Proportions were calculated into a generalized table of ideal male measurements. These measurements used divisions of the chest and waist measurements to draft a balanced layout of the wearer. These mathematical systems were popular between the later half of the 1800s and the 1950s. As a technological advancement of the Industrial Revolution, the tailoring systems allowed anticipations in profit margins and reduced steps requiring the customer's presence, according to Robert Doyle on page 472 of The Art of the Tailor. Although helpful in many ways, the results were often inaccurate and were by no means an exact science in the creation of men's made-to-measure clothing.

Three of these systems were used to determine the size of the intended wearer, as well as to compare and contrast differences among these methods. Those used were the Blue Book of Men's Tailoring (1907), The American Garment Cutter (1924), and The Modern Mitchell System of Men's Designing (c.1930, reissued by Frank Doblin in 1974, 1984). Although two of these systems postdate the garment, both include a frock draft acknowledging that they are from earlier sources and editions, and are included more for tradition than current fashion. For the modern figure all three drafts produced similar outcomes with the most discrepancy and design flaws in the neck and lapel areas. The truest results for comparison to the original article came from the double-breasted frock draft from The Blue Book of Men's Tailoring.

Reproduction

In reproducing this garment, discrepancies in proportion had to be taken into consideration. The original garment, by applying rules of ease across a chest measurement, would likely have been for a man with a 34-inch chest. A diminutive chest measurement by today's standards, resizing the garment presented some challenges. For a modern man with a 41-inch chest, directly applying the same construction methods poses some discrepancy in overall appearance of the garment. The drafting systems often assumed an ideal ratio between the chest and waist size. The waist generally measures five inches less than the chest. With this in mind, the coat can then be darted on the sides and shaped at the waist to produce a sleek silhouette of thin waist and broad shoulders. A man with a 41-inch chest and a 37-inch waist gives a somewhat boxy outline. In 1910, this figure would be considered "stout" whereas a 40-42 inch chest might be considered quite corpulent. Aside from size, assumptions had to be made in the pattern development regarding incremental scaling of lapel lines and overlap of the double breast portion. In the reproduction an amount of 1/2 inch was added to both areas. The top of the lapel's facing turn-back was dropped by 3/4 inch making the collar longer by the same amount. These changes balanced the lay of these points to fall at proportionately more appealing intervals throughout the coat. Although the drafting systems make little mention of these gradations it is likely that certain standards were passed from master tailor to apprentice, thereby omitting these details in available text. Overall, the construction of this coat was congruent with the original. All methods were duplicated accordingly, and all fabrics chosen were as close as the original as available.

© B. Daniel Weger, 2009