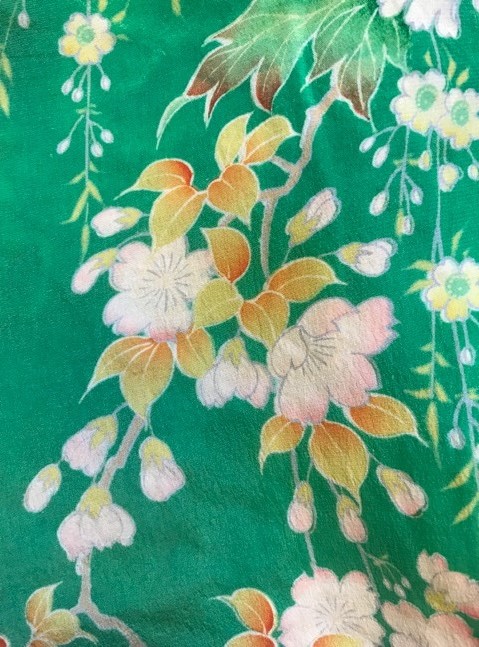

Figure 1: Kosode Front |

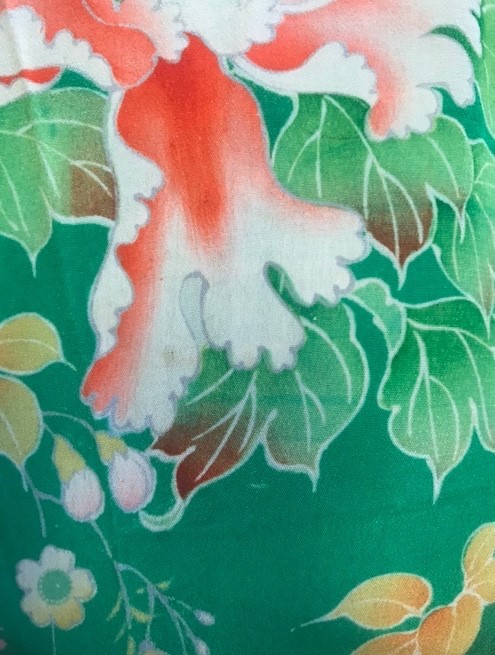

Figure 2: Kosode Back |

|

|

The kosode in Figures 1 and 2 above originated in Japan. It has a summery green background and an array of flowers. On the front, the flowers start from the top of the shoulders and flow down to the bottom of the garment. The back is similar pattern to the front with slightly less decoration (which an obi would obscure). The flower patterns are generally symmetrical, but since the design was done by hand using the Yuzen technique they vary slightly and realistically depict nature.

This kosode is made from silk, an expensive material that has a luxurious feel next to the skin. It also is highly desired because it so lightweight that it makes the harsh and hot summers more bearable and is also such a free-flowing material that women can move in with ease. Silk shows wear after long periods of time in part due to the chemical reaction that occurs when it comes into contact with the alkali in detergent, and from body salts and oils that cause it to deteriorate. As a result, the delicate nature of silk leads to these tears and imperfections in the garment. This kosode in particular has numerous places that have deteriorated. Along the sleeves, the material is shredded as seen in Figure 3 and the China silk lining is disintegrating in many places (see Figure 4 below). Since this garment was so beautifully made, it has more than likely passed down from generation to generation before being donated to the NowesArk Study Collection. It is too fragile to be worn but can nonetheless be studied and appreciated.

Figure 3: Detached Seams |

Figure 4: Lining Deterioration |

|

|

To determine the season of year this kosode was created for, colors play an important part. This kosode is a rich green on the outside and a lighter green ilining. The flowers are a variety of reds, purples, and oranges and the leaves were dyed with yellows, greens, reds, and oranges. The combination of colors suggest that the garment may have been made for the late summer or early fall when the leaves begin to change but flowers remain vibrant and bright colors.

The garment was very clearly dyed using the Yuzen dyeing technique that was developed in the Edo period. As one can see by the white in the undyed parts of the flowers, the garment was originally white before it was dyed. Therefore, the garment was completely dyed to create the palette it now has As in Figure 6 (and others), there are lines showing the outline of each flower and vine on the kosode that separates the color of dyes. In fact, some parts of the garment show the mistakes made in the dyeing process. As seen in Illustration 8, the dye seeped across the line instead of staying within it. These imperfections verify that it was handmade and the dyeing technique allowed its artist to create extremely detailed and vivid graphics on the silk.

Figure 5: Pattern on Sleeve |

Figure 6: Pattern Detail |

|

|

Rather than depicting the flowers, leaves, and vines as superficially facing up and against gravity, the artist chose to paint them in the way they would be seen in nature which follows the Tsukesage ideal. The petals and leaves that point downwards ad seem to gracefully fall, as they would be in the natural world, as seen in Figures 5 and 6 above. Therefore, this way of drawing them shows how so much emphasis these artists placed on being aware and appreciative of nature in its raw form. The small flowers on the kosode seen in Figure 8 are plum blossoms which symbolize spring. The larger flowers in Figures 7 and 9 appear to be chrysanthemum. Chrysanthemum normally symbolize the fall which is when they normally bloom but they can appear -- and be worn -- year-round. The combination of the chrysanthemum with the plum blossoms hint that the garment was more than likely used in the summer. Additionally, as seen in Illustration 9, the leaves are beginning to brown as they do in early fall. Thus, this pattern is fitting for the end of summer into early fall. The flowers begin at the top of the robe and fall nicely all the way down the front and back of the robe. Since they are done by hand, none of the flowers are the exact same, nor are they perfectly symmetrical on either side. Rather, they show the way flowers look.

Figure 7: Flower Detail |

Figure 8: Flower Detail |

Figure 9: Flower Detail |

|

|

|

For this kosode in particular, some of the measurements are slightly different than the standard measurements of a kosode. In the kosode being analyzed, the sleeve depth measures 24 inches from top to bottom. According to most sources including Norio Yamanaka in The Book of Kimono, most kosodes’ sleeve depths measure around 19.5 inches. Additionally, this kosode measures 51.5 inches from top to bottom whereas the standard approximations are 62 inches. Therefore, this kosode has slightly longer sleeves and shorter length. The kosode has a few differences in the lengths, but still remains similar to the standard kosode. When analyzing the pattern closely, one can see in Figure 10 below that the pattern of flowers abruptly ends at the bottom of the sleeve. In all other places of the garment, the leaves and flowers taper off in an elegant and natural way but here, they simply stop in the middle. This raises the possibility that the were shortened from a furisode length to a kosode length. A furisode is a version of the kimono that has longer sleeves which usually measure 39 to 42 inches in length. On this garment, the sleeves would have been cut nearly in half to be 24 inches long. Women traditionally wore a furisode prior to marriage after which they could convert their garments into the appropriate length for a married woman, instead of obtaining an entirely new garment. The conversion from a furisode to a kosode is very easy and was common among women. This conversion furthers the versatility and longevity of these types of kimonos.

Figure 10: Evidence ofShortened Sleeve |

|